Arches were probably first used for buildings in ancient Mesopotamia. They can be built by placing stones, preferably of a wedge shape, forming a semicircle, where the stones support one another by their mutual compression and cannot fall down. However, the whole structure exerts considerable pressure on the sides of the stones at the ends. A set of arches of the same size can be put behind each other, forming a vault that can be used as the roof of a long building. The whole structure is usually cemented with some type of mortar. This type of roof is called a barrel or tunnel vault. Since the side pressure of the vault arches is exerted all along the base of the vault, the supporting walls must be made very strong to withstand this horizontal force in addition to the weights [2]. Barrel vaulting was widely used in the ancient world. An early Roman example is the vault of the sewer of the city of Rome, the Cloaca Maxima, constructed in the third century BC.

The Romans are credited with developing the groin vault, which consists of the intersection of two barrel vaults at right angles (See figure 1). The groin vault channels the forces of the vault into the four bottom corners, allowing spaces to be opened on the side walls in between the support points [3].

A good example of the use of groin vaulting by the Romans is in the Markets of Trajan, built around 110 AD. This was a large complex with different structures. The one shown in figure 2 has a set of groin vaults in line, with their side arches open to provide light and air. This takes advantage of the fact that it is possible to construct groin vaults that are only supported at their corners, as indicated above. [4].

Small round domes had been built earlier, but the Romans significantly developed the technology of building large domed structures. The best example of this is the Pantheon, built around 125 AD by emperor Hadrian.

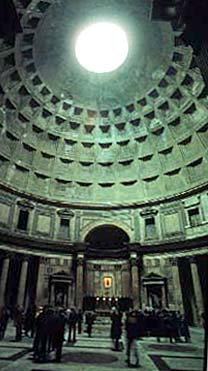

A dome can be understood as an arch that has been rotated 360 degrees around a center point. Thus it exerts strong outward pressures as the arch does, but around its whole circumference. The Romans used a number of techniques in the Pantheon to handle this problem. As can be seen in figure 3, there is a set of concentric stepped rings on the lower part of the dome that act as buttresses, and help handle the outward forces all around [5]. As can be seen in figure 4, the walls of the dome have indentations forming square panels or “coffers” which reduce the weight of the dome as well as being decorative. The open top or “eye” also reduces weight. But the most important technical factor in the Pantheon is the fact that the dome is built of concrete, and the concrete used is of lower density as it reaches the top, also reducing the weight of the dome [6].

Concrete had been used before the Romans, but they perfected it and used it extensively. Concrete consists of a mixture of small stones, sand, lime and water. It is strong and easy to use since it can be poured into a form. It is interesting to note that Vitruvius describes the use of concrete in detail in his writings, which were available throughout the Middle Ages, but its use was not understood or applied again until the 1700’s.

[1] Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge U. Press, 1999), 21.

[2] Talbot Hamlin, Architecture through the Ages (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1953), 14.

[3] Robert Calkins, Medieval Architecture in Westerrn Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 1-3.

[4] William L. Macdonald, The Pantheon: Design, Meaning and Progeny (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976), 57-58.

[5] Ibid., 33.

[6] Ibid., 43.

Figure 1: Groin Vault Diagram

Figure 2: Groin Vault at Trajan Market

Photo © wings.buffalo.edu/AandL/Maecenas

Figure 3: The Pantheon: Exterior

Photo © wings.buffalo.edu/AandL/Maecenas

Figure 4: The Pantheon: Interior

Photo © wings.buffalo.edu/AandL/Maecenas